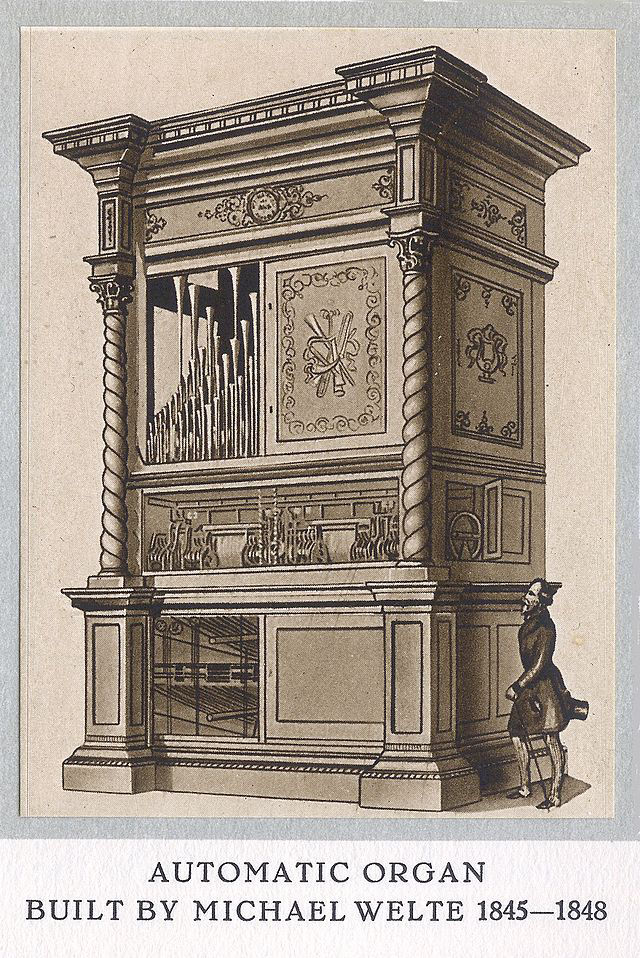

The Welte factory in Freiburg around 1912 and after the Second World WarWhile the US branch of Welte kept building philharmonic organs, there was no comparison with the quality of the ones built in Germany. And although other companies in the US, like Aeolian, started to build philharmonic organs and even exported them to Europe, the Welte instruments were undeniably the most elegant ever built. Later instruments were built to be bigger, but Welte’s quest for musical perfection was not to be repeated.

Today, only a few philharmonic mechanical organs survive. The ones without keyboards are the most rare. The instruments were designed for specific rooms, so they often came without a case, making them vulnerable to damage. Many were destroyed after the advent of electric amplification a few decades after the mechanical organ’s heyday. And as the paper rolls containing the music disappeared, there was little point in restoring the damaged organs as there was no music for them to perform anyway. Their size also prevented most museums from being able to host them.

Most of the surviving instruments were saved because proper organ cases were built for them at the time of their removal from their original locations. The Welte organs that exist today include the one that was built for the Britannic passenger liner. It still works and performs for visitors to the Museum of Music Automatons in Seewen, Switzerland. Another one is still used in the Victorian Theatre at the Salomons Estate in Tunbridge Wells, England – although this one has a keyboard. Another survivor, against all odds, is the Walker organ.

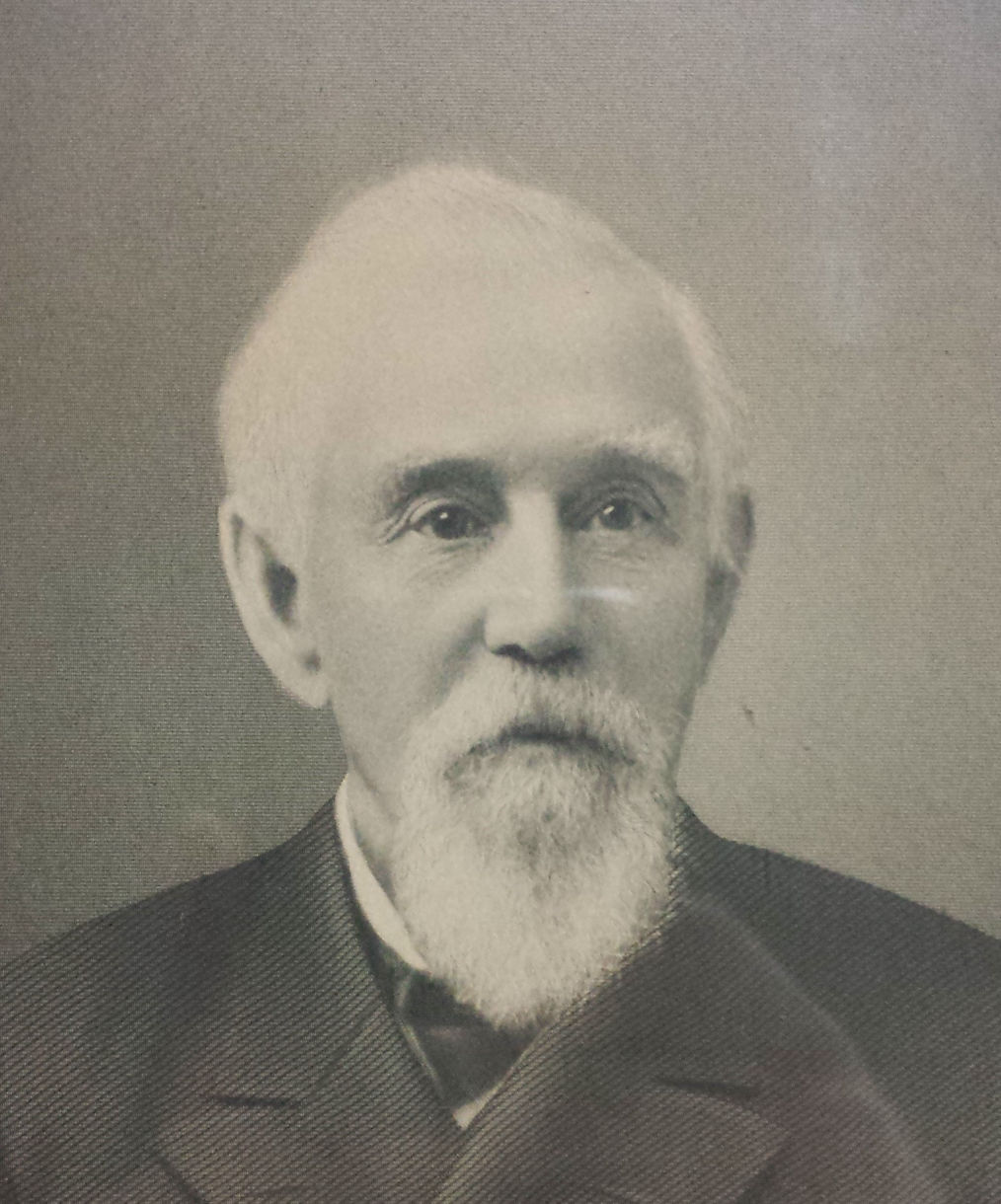

James Harrington Walker died in 1919 after which the family’s Magnolia house changed ownership several times. As the instrument was located in its own special room, subsequent owners of the house did not move or try to fix the organ. It seems that the instrument did not work for very long after it was built and the lower part has suffered from flood damage.

Then in 1998, Mr Durward Center, a rare specialist and restorer of Welte organs from Baltimore, heard that the Walker instrument was to be removed and probably destroyed. Mr Center contacted the owner of the Magnolia house and agreed to come and dismantle the instrument. As it had never been touched, he found all the pipes and mechanisms to be in their original condition. Mr Center took several pictures as the organ was dismantled and he stored all the pieces carefully in Baltimore.